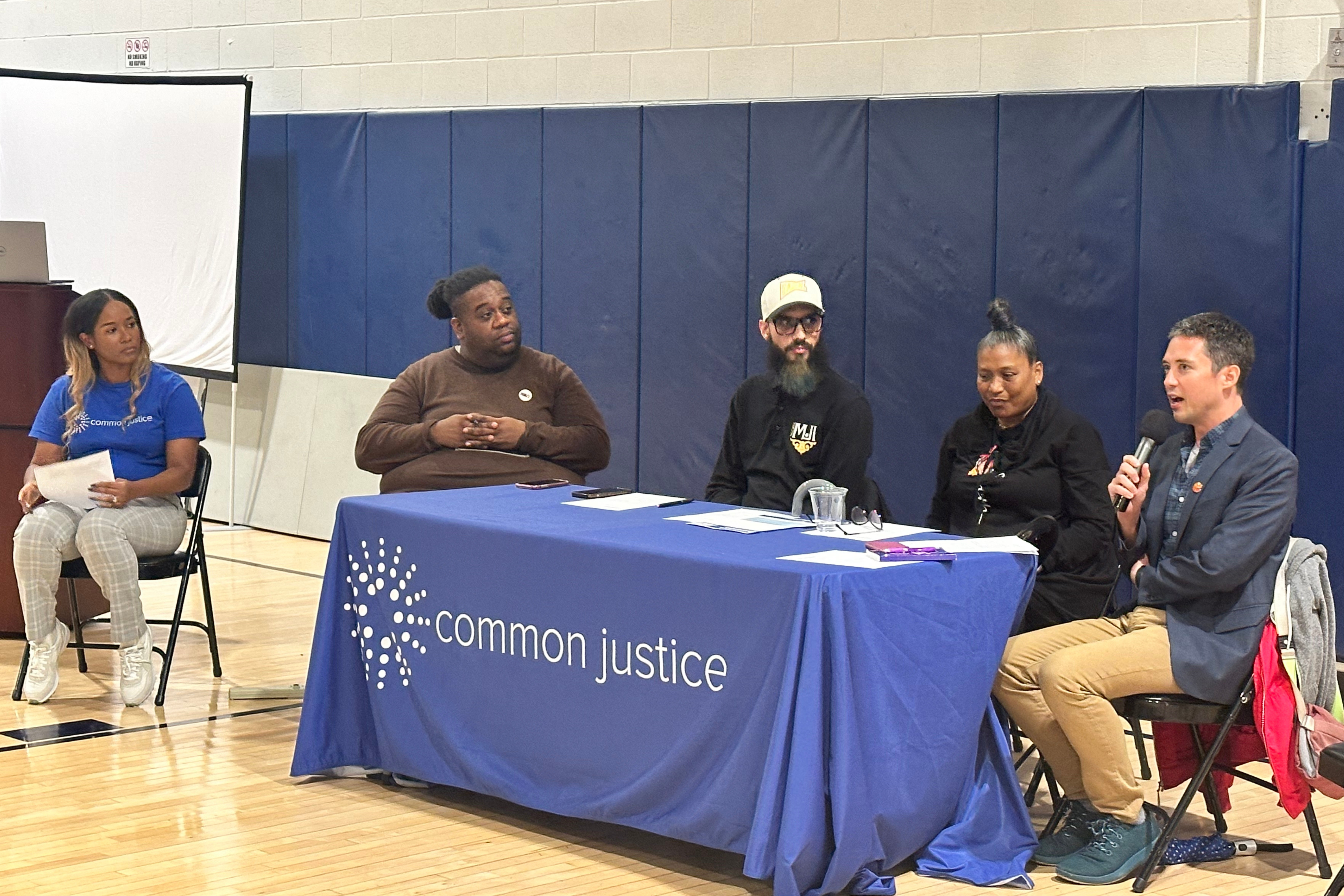

Over the last two years, Common Justice led the organizing and advocacy campaign for Fair Access to Victim Compensation, which seeks to eliminate institutional barriers to victim services so all survivors can have the opportunity to heal. On September 27, Common Justice hosted a town hall, “Healing Beyond Barriers: A Conversation on Fair Access for Survivors,” at Prince Joshua Avitto Community Center in East New York, which brought together survivors and victim service providers to raise awareness about the fight for access and pressure Governor Kathy Hochul to sign this legislation into law. Panelists included (alphabetically) Jeremy Arce of Man Up! Inc, Anthony Buissereth of KAVI (Kings Against Violence Initiative), Peggy Herrera of Not Another Child, Jimmy Meagher of Safe Horizon, and Shneaqua "Coco" Purvis of Both Sides of the Violence, with Sherrell Richardson (Common Justice) as moderator. This blog is a reflection on that event.

In theory, the New York State Office of Victim Services is designed to provide critical financial relief and support services to victims and survivors of violence. In practice, most survivors do not have access to compensation because they were not aware it exists, or worse, they are not considered a “victim.” According to the OVS, only “innocent victims of crime, certain relatives, dependents, legal guardians and eligible Good Samaritans” are qualified to receive these services. There should be no criteria for anyone who wants to heal.

The barriers to victim services are some of the major failures of the existing OVS system. One of the panelists, Peggy Herrera, is a survivor who lost her son, Justin Baerga, to gun violence in July 2022. Currently, she is a Youth Counselor and Recreational Coordinator with Rising Ground. Turning her pain into purpose, she became an advocate to end gun violence with Not Another Child.

“I'm tired of begging for something that is rightfully ours,” Herrera said. “It's ours. Why am I begging you for something? Why add more trauma to us? I should not be calling them if there's a death or a situation in our families. They should be calling us. They should be asking how they can help us instead of us having to always run to them and begging them. Then they've got a thousand stipulations saying well you need this, and you need that.”

Not only do victims have to navigate the difficult emotional terrain of grief, but they also must jump through hoops of bureaucracy which requires them to “legitimize” their pain.

OVS Data from 2018 through 2020 revealed that Black, Latinx, and American Indian/Alaska Native victims were less likely to be awarded compensation than white people. Even earlier data from 2015 through 2019 demonstrated that while Black survivors represented 31 percent of all claims for compensation, they represented nearly 50 percent of all award denials for failure to cooperate with law enforcement.

“Why is there always enough money to fund the systems that oppress us?,” Herrera asked with frustration. “But there's never enough money for survivors, for those of us in our communities that are impacted by so many issues, like poverty and violence. The people that are sitting up putting these bills and rules in place, they know they have access to this. They have access to all these funds and all these resources, and we don't. We're not educated on that.”

According to OVS data, less than 3 percent of all assaults reported from 2018 to 2020 led to claims for compensation. For survivors who are aware of the services, the police requirement is another significant deterrent to compensation because they feel it may expose them to additional harm. For instance, victims who are immigrants fear that calling the police may lead to their deportation. In other instances, police officers were involved in the cases themselves which made victims even less likely to come forward.

“I've worked with survivors whose abuser was a police officer or a police sergeant,” Jimmy Meagher, Policy Director at Safe Horizon, shared. “Or whose abuser was a sibling, a cousin, a best friend. Going to the NYPD was a non-starter. When survivors do try to do the “right thing,” police do not take their story seriously.” The FAVC bill will mitigate these challenges by removing the police reporting requirement altogether and expanding the type of evidence required.

In 2002, Shneaqua "Coco" Purvis lost her sister, Maisha "Pumpkin" Hubbard, to gun violence. With over a decade of organizing to end gun violence, Purvis founded Both Sides of the Violence, which offers preventative, reactive, and restorative solutions to all types of violence for all parties involved. At the Common Justice Town Hall, panelist Purvis spoke about the lessons she learned while working directly with the person who harmed her sister.

“With both sides of the violence, it's not just about victims,” Purvis explained. “Which I am a victim, so don't get it twisted. We are victims, but [those who commit harm] are victims too. How do we break up that yin and yang? How do we break up that relationship? And not be scared to talk about it and address it.”

The problem with the stringent criteria for accessing OVS services is that this “eligibility” is used to limit, rather than maximize access to compensation. Not only does healing become an exclusive benefit reserved for a select few, but also victims are retraumatized as they are subjected to harsh character judgments.

As Jeremy Arce, Director of Crisis Management at Man Up! Inc., advised, “We need to redefine what the ‘perfect victim’ is. The perfect victim is our youth, our members of our community, anybody, because we know it's intended for them students and them kids to have them in our neighborhood. It's designed that way. Everybody is the perfect victim in our neighborhood. Everybody needs to have access to these resources.”

We must continue the fight to ensure compensation is accessible for all, and that means putting the pressure on Governor Kathy Hochul to sign this critical piece of legislation into law.

“Healing is not a privilege, it is a right,” Councilmember Mercedes Narcisse said in her remarks at the Town Hall. “At the end of the day, we are here, we are in this together. We have to uplift those who need it. In order for us to get things done, unfortunately, even if it's the right thing to do, you have to go in people's faces. You have to organize. You have to rally.”

Submit a Comment